I jotted many of these thoughts down across this last term, from between the cracks of dissertation writing and thinking. It is not until now that I have found the calm to string them together.

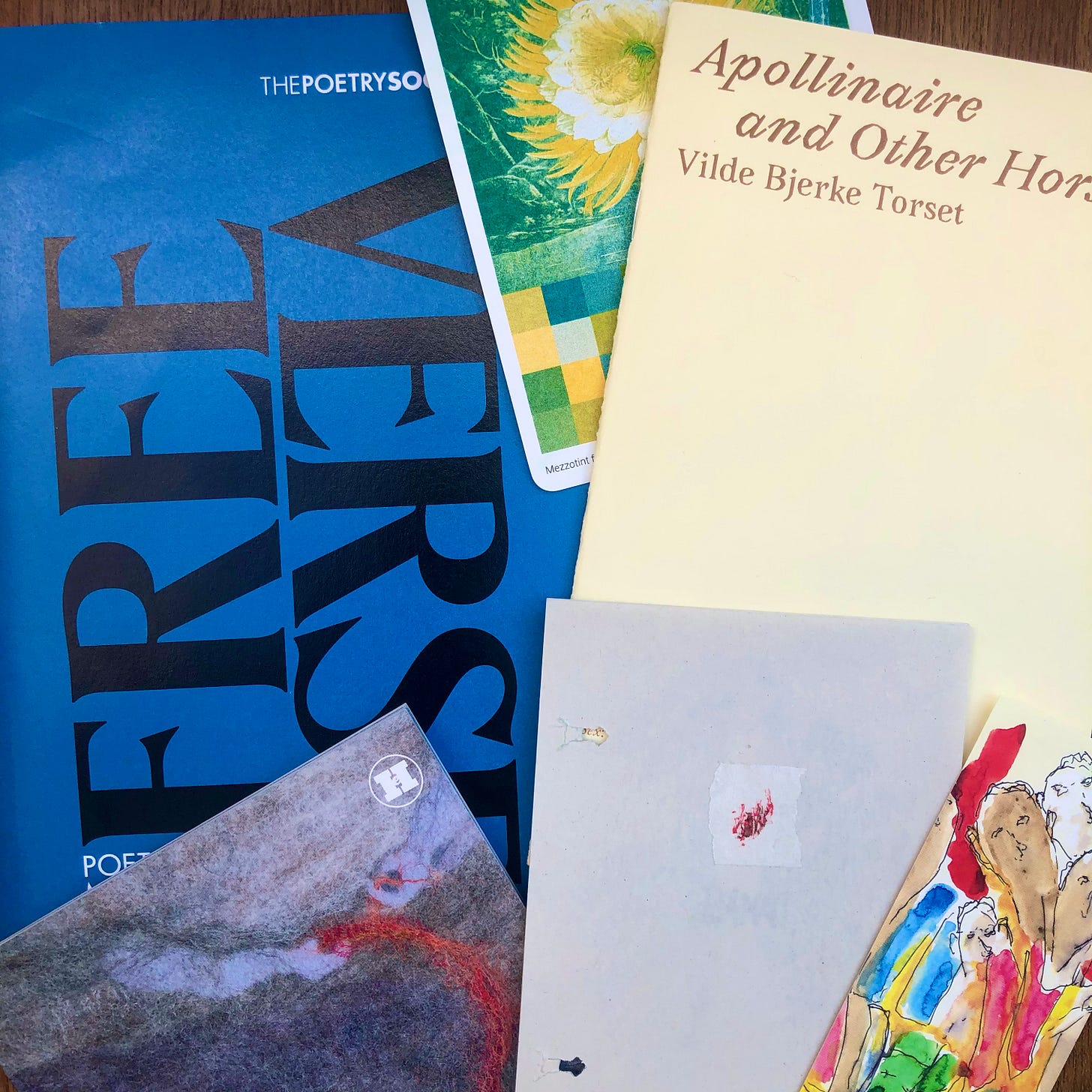

On the last Saturday before term properly picked up again, Sam, my mother and I went to the Free Verse Poetry & Magazine Fair in London. Held in the (very crowded) basement of a church in Chelsea, the fair was host to over seventy magazines and small presses exhibiting their work. It was so enlivening to be in a space filled by so much creativity; the genuine commitment to and respect for the writers they were representing was palpable in the attention to detail and throughout the conversations I had.

I tried to be restrained in my book-buying but (of course) couldn’t always resist. Since then, I have been reading and admiring my purchases. In the hustle & bustle of the fair, the decisions of which books to take home with me were guttural—thankfully my instincts were good that day because the books have been brilliant and touching and surprising in equal measures. What follows are my musings on (a selection of) them.

Morley House

I was drawn to the Morley House stall the moment I laid eyes on it. With their limited-edition artist books laid out in a grid, rather than stacked, their publications had a commanding quiet about them. Their recent book, The Library, took up most of their table space: simple white covers and individually handwritten titles, each book felt like a unique iteration of a continually repeating pattern. Created during an artist residency at the Henry Moore institute, the book moves through the private mind to the library, a public depository of information, and considers how those spaces engage with one another. The story of healing from personal wounds by inhabiting the library is told through evocative, strange drawings & words (by Christos Kakouros & Diana Asadulina—the creative duo behind Morley House).

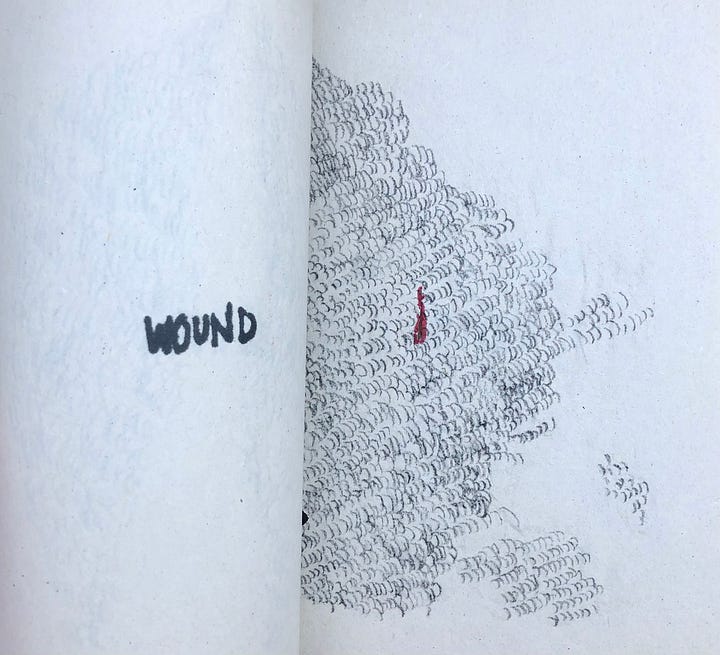

There was a small, inconspicuous book on the corner of the table, titled Damage, Wound, Repair. Made from delicate grey paper with a hand-drawn red mark on its cover, the physical form of the book perfectly translates the stages of hurt and healing it describes in its contents. When picking out the copy to take home with me, Kakouros encouraged me to reach for the red mark that spoke to me the most. It is held together by two small tears in the paper that are tucked back into the pages: binding the book with a wound of its own. A drawing by Kakouros’s accompanies each word of the work’s title; the hurried, yet sensitive, lines capture the chaos and fragility inherent to the three stages. The paper of the ‘wound’ drawing is itself cut and red spills through the paper onto the word ‘repair’, printed on the underside of the leaf. The wound still bleeds into its healing: no repair is clean-cut.

Damage, Wound, Repair concludes with a poem by Asadulina:

‘For now,’ one said

‘You cannot fly for now’

For the time being

… the time being what?

The time being all yours.

At your disposal.

Use it.

The space.

The time.

The now

A hopeful note; a call to action. The book ends by commanding us to use the space, the now, the damage, the wound: to make something without being granted the permission of the right time or place.

I am in awe of Morley House’s creative craftsmanship and will treasure this little book for a long time.

If a Leaf Falls Press

Edited by Sam Riviere and designed by O. Tong, If a Leaf Falls Press produces stunning chapbooks in limited batches. Connecting with my inner horse-girl, I immediately picked up Vilde Bjerke Torset’s Apollinaire and Other Horses. Drawing from Apollinaire’s horse-shaped calligram, Torset poetically traces a real-life race-horse named Apollinaire. In equal parts funny and touching, Torset’s chapbook is a brilliant meditation on the peculiar minds and beings of these creatures.

One of my favourite moments in the project is the inclusion of a pair of emails exchanged between the poet and Apollinaire’s trainer, Ralph M. Beckett. The formality of the emails is contrasted with the lightness of their contents, making them playful, strange interjections. In answering the question about ‘his journey, or temperament, or favourite snack?’, Ralph M. Beckett reveals that Apollinaire often goes by Apples or Polly and particularly enjoys carrots. With only a couple fragments of information, Apollinaire is transformed from a list of stats (‘Sex: Gelding / Colour: Bay / Form: 222/85433’) to a living creature with likes and dislikes and habits.

I love horses: the way they move and their stubborn, anxious, gentle demeanours. I think it’s wonderful how stinky they can get on a hot summer’s day, and the joy they find in rolling around in the dry dirt. My grandfather kept Haflingers after he retired; he passed away before I was born, but I was always captivated by the stories and pictures of him with his horses. One of the main reasons I desperately wanted horse-riding lessons stemmed from a romanticised idea of making him proud. There was one horse I used to ride who was very nervous—a shadow in a particular corner of the paddock spooked him once and every subsequent time we passed that corner, I could feel the stress in his body. Even on different days, with different light and different shadows, he registered the feeling of fear he first felt when the shadow moved in an unexpected way.

One of Torset’s poem’s, ‘the taming of Bucephalus’, captures this anxiety perfectly. Bucephalus, Alexander the Great’s horse, was afraid of his own shadow. As legend goes, Alexander soothed him by turning his head toward to sun, thus shielding his eyes from himself.

he’s big and he’s wild and he’s caught the eyes

and the eye says a massive creature

says with a massive head

is not a bad thing even if you’re not an ox

but have one branded on your butt

just calm down you mentalist says eye

says the eye says eye know what to do

says turn around old boy

look says the shadow is gone says

you’re safe have a polo have two even

The name, Bucephalus, comes from the bulls-head-shaped scar on his thigh. A pair of ever-watchful eyes. Torset’s oppressive repetition of ‘eye’ captures the darting, suspicious eye of the horse and the anxiety of over-vigilance that melts into the personal pronoun, ‘I’. The voices of the bull, Bucephalus, and Alexander dissolve into one another, creating a slippery cacophony of instructions: ‘says eye / says the eye says eye’.

Hercules Editions

At the heart of Hercules Editions lies a dedication to storytelling through the combination of textual and visual elements. My pick from their collection was The Nine Mothers of Heimdallr by Miriam Nash, a long(ish) poem that gives voice to Norse Mythology’s matriarchal figures. Nash’s words are accompanied by a series of textile artworks created by her mother, Christina Edlund-Plater. I read this little book on the 12th of May, Mother’s Day (for those of us who are not English, at least), sitting in my garden and thinking about my own mother.

The Nine Mothers of Heimdallr re-tells the story of the giant-sisters who collectively bore Heimdallr, the son of all nine women equally. The poem is voiced by the mothers collectively telling Heimdallr of his own history and how he, and the world he exists within, came into being.

Gjalp carried you through blood

Greip carried you through blood

and Atla carried you through blood

and Eistla carried you.

Angeyja carried you through blood

Jarnsaxa carried you through blood

Eyrgjafa carried you through blood

and Ulfra carried you.

And child, I [Imthr] carried you through blood

your tiny body close to mine

we bore you in our giant arms

and so became your mothers, nine.

This story speaks beautifully to the sentiment that there is no one way to be a mother, nor is motherhood an easy, containable category. The mothers tell Heimdallr about Ymir, the primeval giant from whose body the world was made. A being who is both mother and father at once:

Ymir was frost was wind was flame

Ymir was form was voice was name

Ymir, the giant, the first, became

our mother-father.

Heimdallr similarly has to contend with doubleness, apparent contradiction, in his identity: ‘Am I a giant or a god?’ His father being Odin, there is a split in his roots.

I don’t want to be a god

I don’t want to be a half

Ymir was mother-father, child

Both might be your path.

Edlund-Pater’s artworks made from felt capture the fluidity that runs throughout the poem. Fabric strands intermingle with one another, interweaving to express the changing and changeable landscape of the poem.

This pairing of textile and text makes me think of my own mother, Marian de Vooght, who herself is a poet and textile-artist. I feel very privileged to have been able to watch her develop her latest project (Taglines) from the collection of clothing-tags to the exhibition of the pieces. She taught me the values (and practicalities) of mending, the wonder of words, and how no one creative pursuit exists in isolation.

p.s. other magazines and presses I particularly loved from the fair include: earthbound press, Butcher’s Dog, Magma Poetry, zimZalla, And Other Stories, Smokestack & Prototype

What a great fair it was! I love how you made these great choices, the books you bought, and how you touch their beautiful, ephemeral tentacles and connect them to your brain, the person you are.

Beautiful